Ebola Health Care Worker Sick Because Safety Rules Were Not Followed, Officials Say

A Dallas health care worker who has been diagnosed with Ebola got sick because safety protocols for treating a man who later died from the disease were not followed, health officials said Sunday.

The unidentified health care worker at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital who tested positive for Ebola wore full protective gear while she cared for Thomas Eric Duncan, a Liberian man who died from Ebola on October 8. But just wearing the gear isn't enough to avoid danger, according to health officials who suggested that contamination could have occurred while the health care worker was putting on or taking off the protective gear, which consists of a gown, a mask, gloves, a face shield, and booties.

"We don't know what occurred in the care of the patient in Dallas, but at some point there was a breach in protocol," said Thomas Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Dallas health care worker's illness is a reminder of the risks medical personnel have faced during the Ebola outbreak that began in West Africa, and of how U.S. health officials have been scrambling to try to ensure the safety of medical personnel who may come in contact with Ebola patients.

At least 416 health care workers have been infected with Ebola in West Africa this year and 233 have died, greatly limiting the care options there, and the willingness of others to provide that care. In total, more than 8,300 people have been infected by Ebola this year and about 4,000 have died. Health care workers in the West typically are better protected from contagious diseases than those in Africa, because Western workers and hospitals have the knowledge and equipment to shut down the spread of infections.

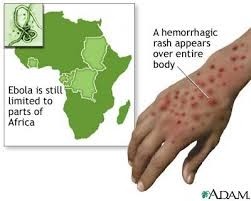

But the outbreak of Ebola—which is spread through close contact with symptomatic person's bodily fluids such as blood, vomit, feces, or semen—is raising questions about just how prepared U.S. health care workers and hospitals really are.

Ashish Jha, professor of health policy at the Harvard School of Public Health, said medical protocols have to be followed meticulously to protect health care workers from Ebola.

It's not yet clear specifically how the Dallas health care worker became infected, but Jha said it likely occurred when she was taking off her protective equipment, which he said has to be done very carefully to avoid contamination. At the most well-run Ebola treatment units in Africa, a staff member is responsible for watching other workers, particularly when they take off their gear, to make sure no one comes in contact with the outside of the gear.

"Any system that assumes that human beings will make zero errors is not a very good system," Jha said. Frieden, the CDC director, said he's counseled Texas Health Presbyterian to have such a staff member be responsible for watching colleagues and making sure they don't have any more lapses in protective procedures.

CDC Sends More Staffers to Texas

During a news conference Sunday, Frieden—who is awaiting tests to confirm the health care worker's infection—also said he is recommending that any hospital treating Ebola patients keep the number of caregivers and procedures to a minimum. He added that the CDC has sent additional staff members to Texas to assist in the U.S. government's response to the Ebola situation there.

"We're going to look at all opportunities to improve the level of safety and minimize risk," he said. That might include moving the health care worker to another hospital that has more experience taking care of patients with Ebola, he said, although he emphasized that he wants every hospital in the United States to be prepared to diagnose the viral disease and rapidly isolate and treat any patients with it.

The hospital released a five-paragraph statement Sunday that said, "the caregiver and the family have requested total privacy, so we can't discuss any further details of the situation."

The hospital is directing ambulances to take patients to other area hospitals because of staff limitations and is triple-checking its compliance with CDC guidelines, the statement said.

Staff members who were exposed to Duncan during his first emergency room trip there on September 25, when he was sent home, and again on September 28, when he returned by ambulance, already had been asked to stay home and monitor their temperatures.

It is not clear how many more will be added to that watch list now that one of his caregivers was exposed to Ebola. In all, 48 health care workers and others who came in contact with Duncan are monitoring their temperatures twice daily until 21 days after their suspected exposure. Four people who were closest to Duncan during his stay have been asked to stay put at a house donated for the purpose.

"We are also continuing to monitor all staff who had some relation to Mr. Duncan's care even if they are not assumed to be at significant risk of infection," according to the statement signed by Wendell Watson, who directs public relations at Texas Health Resources, the hospital's parent company, which also runs 24 other acute-care, transitional, rehabilitation, and short-stay hospitals.

"All of these steps are being taken so the public and our own employees can have complete confidence in the safety and integrity of our facilities and the care we provide," Watson said. Jha said the public would have more confidence if the hospital were more transparent about what happened and what it is doing to correct its mistakes.

"Arguing patient privacy is absurd," Jha said. "You can share a lot of information about the context without giving away critical information about the patient."

David Lakey, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services, also expressed frustration that a health care worker had not been sufficiently protected against the virus. The hospital has been cooperating with state and national public health officials.

"Is it frustrating or disappointing? Of course it is," Lakey said, of the news conference with Frieden. "It's obviously a very trying day."

It is possible, officials acknowledge, that someone else who helped care for Duncan will develop Ebola. Lakey praised the health care worker who is being treated, saying that she did exactly what she should have done when she realized she might have been infected.

She had been monitoring herself twice a day for a possible fever, Lakey said, and reported to the hospital Friday evening when her temperature began to rise. The only other person who she potentially exposed—while she had symptoms and before she was isolated—was her partner, who has been voluntarily isolated and will be monitored for three weeks, Lakey said.

Airport Screening Begins

On Saturday, the CDC began screening passengers at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York arriving from the three West African nations hardest hit by Ebola: Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. Frieden said the CDC is learning lessons from that roll-out and will expand it to four other international airports, probably on Thursday. The five airports—JFK, Washington's Dulles International, Newark International, Chicago's O'Hare International, and Hartsfield-Jackson International in Atlanta—handle the vast majority of the roughly 150 America-bound passengers who arrive from the three countries each day, Frieden said last week.

Health officials hope the screenings will catch any passengers who might have developed Ebola symptoms since leaving West Africa. Ebola is contagious only after symptoms have developed.

Passengers leaving Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea are tested for fevers and quizzed about any exposures they might have had to Ebola. Duncan was not symptomatic until about five days after he left West Africa. He may have lied on his exit forms, saying he had not had any contact with an Ebola patient. He apparently helped his landlord's pregnant daughter to the hospital shortly before she died of the disease.

After Duncan first went to the Texas Health Presbyterian emergency room on September 25, he was sent home some four hours later with an antibiotic, which would have been ineffective against his viral infection. The hospital has said his symptoms were not severe, but recent news reports suggest he had a fever of 103 while at the hospital and was suffering severe abdominal pain, which would not have been consistent with his diagnosis of a sinus infection. The hospital has issued statements about its handling of the case but its representatives have declined to discuss it in detail with the media.

The unidentified health care worker at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital who tested positive for Ebola wore full protective gear while she cared for Thomas Eric Duncan, a Liberian man who died from Ebola on October 8. But just wearing the gear isn't enough to avoid danger, according to health officials who suggested that contamination could have occurred while the health care worker was putting on or taking off the protective gear, which consists of a gown, a mask, gloves, a face shield, and booties.

"We don't know what occurred in the care of the patient in Dallas, but at some point there was a breach in protocol," said Thomas Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Dallas health care worker's illness is a reminder of the risks medical personnel have faced during the Ebola outbreak that began in West Africa, and of how U.S. health officials have been scrambling to try to ensure the safety of medical personnel who may come in contact with Ebola patients.

At least 416 health care workers have been infected with Ebola in West Africa this year and 233 have died, greatly limiting the care options there, and the willingness of others to provide that care. In total, more than 8,300 people have been infected by Ebola this year and about 4,000 have died. Health care workers in the West typically are better protected from contagious diseases than those in Africa, because Western workers and hospitals have the knowledge and equipment to shut down the spread of infections.

But the outbreak of Ebola—which is spread through close contact with symptomatic person's bodily fluids such as blood, vomit, feces, or semen—is raising questions about just how prepared U.S. health care workers and hospitals really are.

Ashish Jha, professor of health policy at the Harvard School of Public Health, said medical protocols have to be followed meticulously to protect health care workers from Ebola.

It's not yet clear specifically how the Dallas health care worker became infected, but Jha said it likely occurred when she was taking off her protective equipment, which he said has to be done very carefully to avoid contamination. At the most well-run Ebola treatment units in Africa, a staff member is responsible for watching other workers, particularly when they take off their gear, to make sure no one comes in contact with the outside of the gear.

"Any system that assumes that human beings will make zero errors is not a very good system," Jha said. Frieden, the CDC director, said he's counseled Texas Health Presbyterian to have such a staff member be responsible for watching colleagues and making sure they don't have any more lapses in protective procedures.

CDC Sends More Staffers to Texas

During a news conference Sunday, Frieden—who is awaiting tests to confirm the health care worker's infection—also said he is recommending that any hospital treating Ebola patients keep the number of caregivers and procedures to a minimum. He added that the CDC has sent additional staff members to Texas to assist in the U.S. government's response to the Ebola situation there.

"We're going to look at all opportunities to improve the level of safety and minimize risk," he said. That might include moving the health care worker to another hospital that has more experience taking care of patients with Ebola, he said, although he emphasized that he wants every hospital in the United States to be prepared to diagnose the viral disease and rapidly isolate and treat any patients with it.

The hospital released a five-paragraph statement Sunday that said, "the caregiver and the family have requested total privacy, so we can't discuss any further details of the situation."

The hospital is directing ambulances to take patients to other area hospitals because of staff limitations and is triple-checking its compliance with CDC guidelines, the statement said.

Staff members who were exposed to Duncan during his first emergency room trip there on September 25, when he was sent home, and again on September 28, when he returned by ambulance, already had been asked to stay home and monitor their temperatures.

It is not clear how many more will be added to that watch list now that one of his caregivers was exposed to Ebola. In all, 48 health care workers and others who came in contact with Duncan are monitoring their temperatures twice daily until 21 days after their suspected exposure. Four people who were closest to Duncan during his stay have been asked to stay put at a house donated for the purpose.

"We are also continuing to monitor all staff who had some relation to Mr. Duncan's care even if they are not assumed to be at significant risk of infection," according to the statement signed by Wendell Watson, who directs public relations at Texas Health Resources, the hospital's parent company, which also runs 24 other acute-care, transitional, rehabilitation, and short-stay hospitals.

"All of these steps are being taken so the public and our own employees can have complete confidence in the safety and integrity of our facilities and the care we provide," Watson said. Jha said the public would have more confidence if the hospital were more transparent about what happened and what it is doing to correct its mistakes.

"Arguing patient privacy is absurd," Jha said. "You can share a lot of information about the context without giving away critical information about the patient."

David Lakey, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services, also expressed frustration that a health care worker had not been sufficiently protected against the virus. The hospital has been cooperating with state and national public health officials.

"Is it frustrating or disappointing? Of course it is," Lakey said, of the news conference with Frieden. "It's obviously a very trying day."

It is possible, officials acknowledge, that someone else who helped care for Duncan will develop Ebola. Lakey praised the health care worker who is being treated, saying that she did exactly what she should have done when she realized she might have been infected.

She had been monitoring herself twice a day for a possible fever, Lakey said, and reported to the hospital Friday evening when her temperature began to rise. The only other person who she potentially exposed—while she had symptoms and before she was isolated—was her partner, who has been voluntarily isolated and will be monitored for three weeks, Lakey said.

Airport Screening Begins

On Saturday, the CDC began screening passengers at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York arriving from the three West African nations hardest hit by Ebola: Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. Frieden said the CDC is learning lessons from that roll-out and will expand it to four other international airports, probably on Thursday. The five airports—JFK, Washington's Dulles International, Newark International, Chicago's O'Hare International, and Hartsfield-Jackson International in Atlanta—handle the vast majority of the roughly 150 America-bound passengers who arrive from the three countries each day, Frieden said last week.

Health officials hope the screenings will catch any passengers who might have developed Ebola symptoms since leaving West Africa. Ebola is contagious only after symptoms have developed.

Passengers leaving Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea are tested for fevers and quizzed about any exposures they might have had to Ebola. Duncan was not symptomatic until about five days after he left West Africa. He may have lied on his exit forms, saying he had not had any contact with an Ebola patient. He apparently helped his landlord's pregnant daughter to the hospital shortly before she died of the disease.

After Duncan first went to the Texas Health Presbyterian emergency room on September 25, he was sent home some four hours later with an antibiotic, which would have been ineffective against his viral infection. The hospital has said his symptoms were not severe, but recent news reports suggest he had a fever of 103 while at the hospital and was suffering severe abdominal pain, which would not have been consistent with his diagnosis of a sinus infection. The hospital has issued statements about its handling of the case but its representatives have declined to discuss it in detail with the media.

- hc9b073b91be26d7f9edf0916a07c87378.jpg

- ccb1ecfbc7c10e831c8b05ff50457b2668.jpg

Videos

References

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/10/141012-ebola-dallas-healthcare-spread/

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dnyjlWfGBWM

http://i.ytimg.com/vi/wsd0E0ClZZo/hqdefault.jpg

http://www.news10.net/story/news/local/2014/08/19/kaiser-ebola-patient/14316293/